Historical Highlight: Moving Navigation Forward

Moving Navigation Forward

April 10, 1947, Tadeusz Wincenty Szpila throws up his lunch over the railing of a ship — or as he recorded in his diary, “donating to the fish in the sea.”

It’s Day 3 of his journey on the ship Ernie Pyle from Bremen, Germany, to the United States. The day before, the sea had been calm, and he had glimpsed the foggy coast of France from the deck of the Pyle. But today, out in the open ocean, the ship rocks and rolls. “I feel like a feather in one second … and then feel heavy like an elephant,” he wrote.

Where exactly he is, he can’t say — the ship’s daily report to passengers only gives the approximate number of miles the Pyle still had left to sail. He gets used to the ship’s rocking. Days 6, 7 and 8, he checks the report. 2,078 miles to go. 1,668 miles. 1,267 miles. He records the distance in his diary, the distance between two very important points: himself, and his destination, New York City.

In 1947, passengers like Tadeusz Wincenty Szpila relied on the ship’s navigator to calculate the approximate distance the ship still had to travel to reach its destination. There was no GPS, no satellites that could take measurements based on receivers and stations that sit on fixed points on the Earth. A series of equations that underpin that process had yet to be developed by a man named Thaddeus Vincenty, a self-taught mathematician.

For a time during his long career, Vincenty would work for an organization that would become the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and, in his honor, the agency would name its Forward Innovation Center in its new facility in St. Louis, which opened in 2025, after the Forward equation he developed.

But back in the 1940s, traveler Tadeusz Wincenty Szpila must rely on his ship’s report. On Day 11, he lands in New York. From there, Szpila travels to Massachusetts to live with his cousin. Later, he joins the U.S. military, takes correspondence courses at the University of Wisconsin on math and geodesy and moves to the Great American West. He changes his name to a variation that’s slightly easier on the American-English tongue. And Thaddeus Vincenty devotes his life to calculating the exact distances between two points on Earth.

Vincenty was born in 1920, in a small village of Grodzisko Gorne, in the countryside of Poland. His mother taught him to read in his native Polish before he entered kindergarten. He studied Latin and German in school. He taught himself English in his free time, Vincenty’s son, Michael, recalled his father telling him.

In 1937, Vincenty was accepted to a prestigious secondary school to become a teacher. Two years later, German troops invaded Poland. Vincenty left school to join the Polish Resistance, where he wrote, printed and distributed resistance newspapers.

“This was an extremely dangerous activity that would mean certain death if he was ever caught,” Michael said. “He understood the risks, yet he took them. In late 1941, his cell was busted by the secret police. Immediately, my father went into hiding. He left his family for fear of reprisals against them.”

Vincenty, who had a natural talent with languages, spoke German fluently and spent the rest of World War II in enemy territory, under a new identity, Tadeuss Kochanowicz. In Germany, he saw entire cities destroyed, Michael said. In the last weeks of the war, Vincenty witnessed the death of his younger brother in an aerial bombing raid.

In 1945, Vincenty went to live in a displaced persons camp in Heilbronn, Germany. His knowledge of English allowed him to take on important work as a translator between the American, Polish and German workers and members of the camp, said Michael. Vincenty also worked as a 4th grade teacher for the camp’s children, played the organ in the church and directed the church choir. After about two years in the camp, Vincenty was sponsored by his cousin Helen to live with her in the United States and sailed to New York on the Ernie Pyle.

Upon arriving in the United States, Vincenty got a job working on an assembly line, but he found that work tedious.

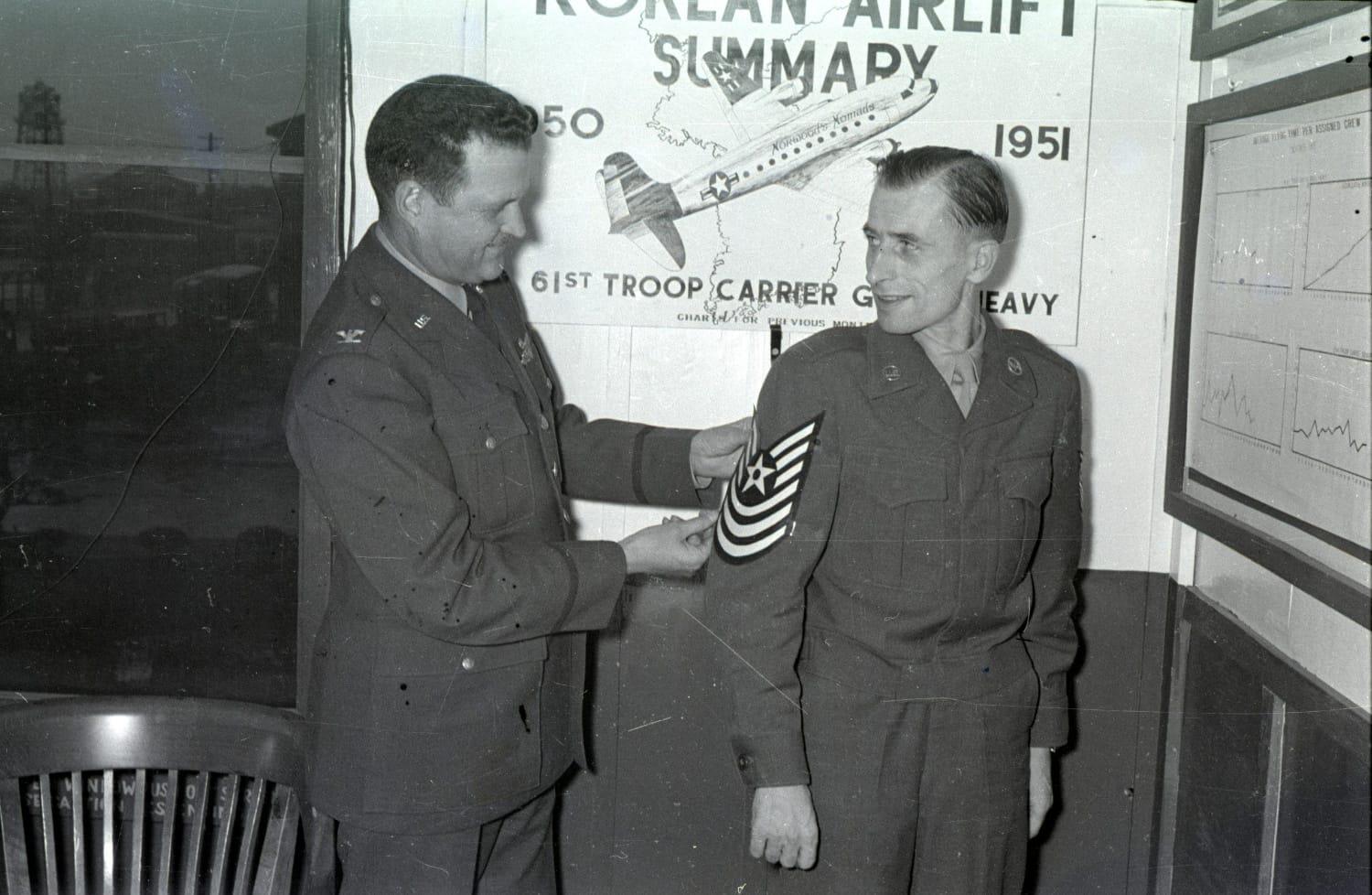

“So one day, after having several beers at the local pub, Dad and his buddy talked it over and decided to join the Air Force,” Michael said.

Vincenty’s Air Force career took him twice to Germany, where he met and married his wife, Barbara. During his second tour of Germany, after some conversations with a fellow airman who performed land surveys, he switched his military specialty to surveying.

With the change, Vincenty immersed himself into the study of geodetic science, or the science of measuring and understanding the earth’s shape, orientation in space and gravitational field — which is always changing. In his free time, he read academic journals. He took correspondence classes with geodesy experts from the University of Wisconsin. He learned how to program new machines called “computers” and wrote his own programs to test his theories and calculations. He published his ideas about geodetic science in both German and English.

Eventually, the Air Force stationed him at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming. He and his family remained there when he retired from the Air Force in 1969 and was recruited to work as a civilian geodetic technician for the Defense Mapping Agency, an NGA predecessor agency.

In 1976, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Geodetic Survey office offered Vincenty a dream assignment: help them update the North American Datum Adjustment 1927, or NAD27. Much to the chagrin of the three Vincenty children — who loved their blustery, free-range lifestyle in Wyoming — the Vincenty family packed up and moved to Maryland.

The North American Datum, or NAD, is the geographical framework for where monuments are located in the United States, Canada and Mexico. These monuments are built into the ground and tell surveyors needing to make exact measurements the latitude and longitude of certain points, allowing surveyors to accurately calculate their own location and distances between points.

The NAD also provides the equations needed, based on variations of the Earth, to make the calculations. Humans exist atop the Earth’s not-perfectly-round surface, and the shortest distance between, for example, New York and Los Angeles, is actually through the Earth’s crust. Because we are not moles, finding the actual distance humans travel along the Earth’s surface requires some serious math.

The first NAD was created in 1927, when there were no computers to perform advanced mathematical calculations, no electronic instruments for precise measurements, and, as the United States was less developed, fewer established data points to work from. By the early 1970s, when the Vincenty kids were still riding their bikes to the roller rink in Cheyenne, NAD27 was nearly 50 years old, and many of the new points added during the past five decades did not “fit” nicely into the existing system. Surveyors complained their measurements were off. Something had to be done, and in 1973, something was.

That year, U.S. Coast and Geodetic Surveys Commander John Bossler, having just finished his doctorate in geodesy at Ohio State University, was appointed to lead the update of the NAD27, NAD83. A few years into the project, a colleague of Bossler’s, Chuck Whalen, who had worked with Vincenty in Cheyenne, recommended to Bossler that NOAA bring Vincenty on. The formulas Vincenty had been developing while working in the Air Force and Defense Mapping Agency might help the update. Bossler, who had seen some of Vincenty’s published papers on geodesy, made the call.

Vincenty arrived at NOAA in 1976 with the project already under way. Vincenty familiarized himself with what had been done and got to work.

Whalen’s recommendation ended up being a great one. Many of Vincenty’s models were incorporated into NAD83, enhancing the mathematical framework for the readjustment. Bernard Chovitz, former president of the Geodesy Section of the American Geophysical Union, called Vincenty “a major contributor of much of the underpinnings” for NAD83, which still forms the basis for surveys performed in North America today.

“Vincenty developed and conceived essential features of that model,” Chovitz said.

One of Vincenty’s contributions was his Forward equation. Forward calculates the location of a point based on a distance and azimuth from another point — “three-dimensional geodesy,” the Department of Commerce referred to it when presenting Vincenty with an award in 1982. Without getting too deep into the math, let’s just say the formula was a very large reason that NAD83 became a significant improvement over NAD27. (Anyone interested can read NOAA’s publication, The New Horizontal Control Datum for North America: NAD 83 at https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/51723 .)

“This formulation he did with NAD83, Vincenty had that in his head and fiddled with it, examined it, wrote that in an article or two that I read,” said Bossler, now a retired admiral. “He was not blessed with a formal education, yet he came up with something just by thinking about it that was pretty good. It’s not relativity-level science, but nobody else had done it. That says a lot.”

The new NAD83 was, and still is, a boon to surveyors, but its impact did not stop there.

“At any given moment on the planet, there are billions of devices being used to navigate the world,” said Mark Munsell, retired NGA director of data and digital innovation. “The devices rely specifically on Vincenty’s formulas, which calculate the location of a point based on a distance and azimuth from another point or the distance and azimuth between two points.

“Vincenty’s formulas are essential for precise, efficient and reliable geodesic calculations in modern geodesy, navigation and geospatial technologies — they make accurate measurements of the earth possible,” said Munsell. “His innovations established a national capability that set the United States apart in its ability to conduct precision strikes, but also improved humanity’s ability to navigate with precision, leading to improvements in the many facets of the global economy.”

That’s why the innovation center in NGA’s new facility in St. Louis was named the Forward Innovation Center, honoring “Vincenty’s enduring legacy in advancing accuracy, efficiency, and innovation in geodesy,” said Munsell.

“Vincenty’s dedication to his craft and country left an impact that benefits us all,” Munsell said. “NGA continues forward movement in innovation, guided by the innovators in our history, including Vincenty. We stand on the shoulders of Thaddeus Vincenty.”

While Vincenty was changing the world at NOAA, his family experienced the “culture shock” of life in the D.C. area. “The traffic, the congestion and the East Coast mentality was very different from the easygoing life of Wyoming,” his daughter, Krysia Moore, said. Vincenty’s children didn’t quite understand what their father was doing at NOAA, or its significance.

“We just knew it involved lots of math, calculations and equations,” Moore said.

Moore said that now, as an adult with more knowledge and understanding of her father’s accomplishments and background, she sees his career in a new light.

“Our dad loved his work, and it was his passion,” she said. “I believe our dad immersed himself in his work as an escape from the horrors of war that haunted him throughout his life.”

Bossler remembered Vincenty coming to his office wanting to bounce ideas around about complex geodetic topics.

“I had a Ph.D. in geodetic science, so he liked to come in and tell me how he was thinking,” Bossler said. “I understood what he was saying, and not everybody could. I was very interested in the discussions — and I liked him.”

For his work on NAD83, Vincenty received a medal of meritorious service from the Department of Commerce. He retired from federal service in 1986 and passed away in 2002.

The bookish boy meant to be a schoolteacher in Poland finished his life as a highly regarded mathematician in the United States. Vincenty’s life was hardly a straight line between those two points — yet he navigated through the tragedy and disaster of war to help make precise, efficient navigation possible for us all.