Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Flashback Friday

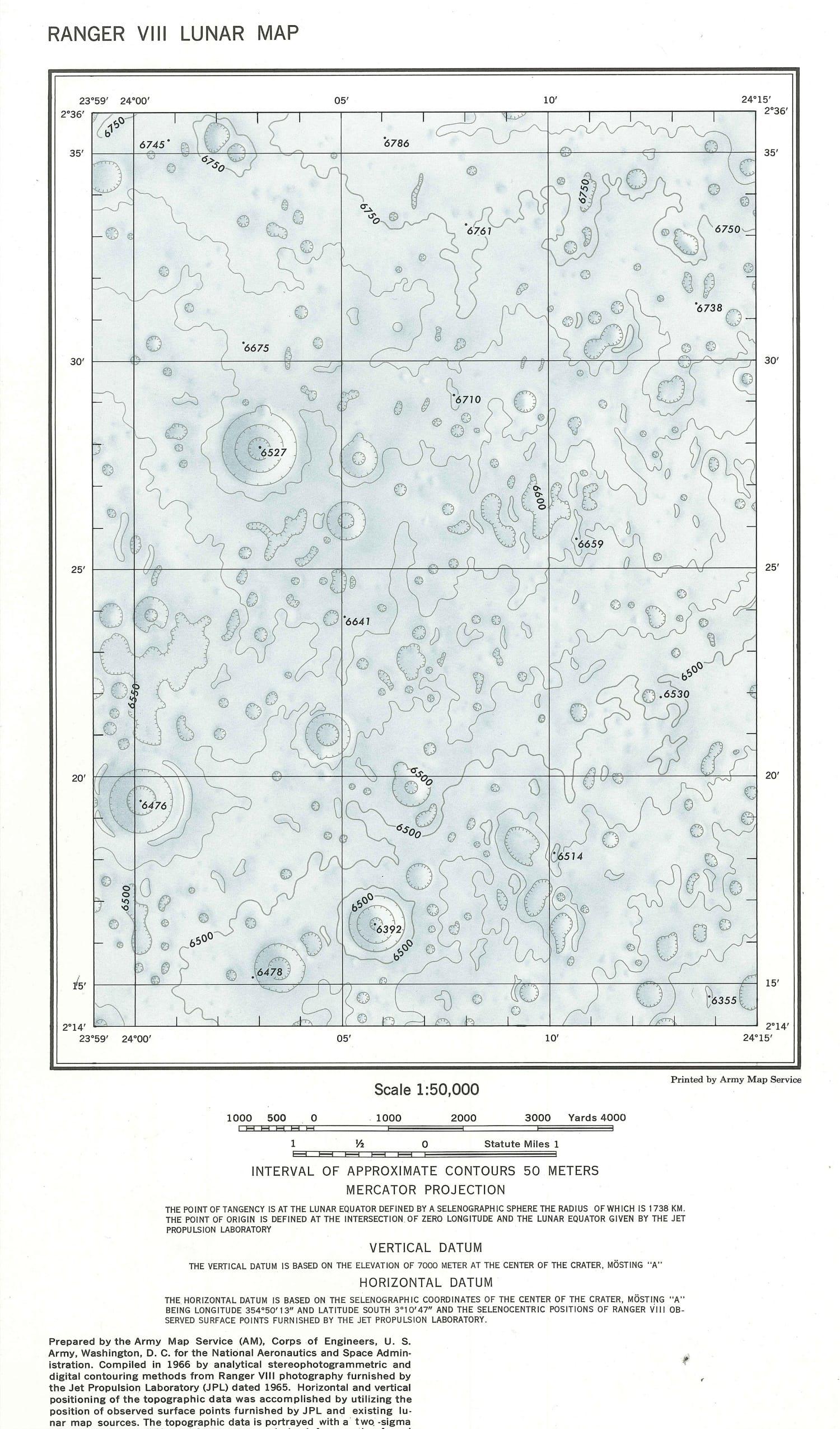

The U.S. Air Force's Aeronautical Chart and Information Center's publication, "The Orientor," chronicled ACIC's contributions to the Apollo 11 lunar mission, which even included a signed lunar mission chart from astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins.

Lunar maps paved way for moon exploration

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy made a promise to the world: Americans would put a man on the moon, and return him home safely by the end of the decade.

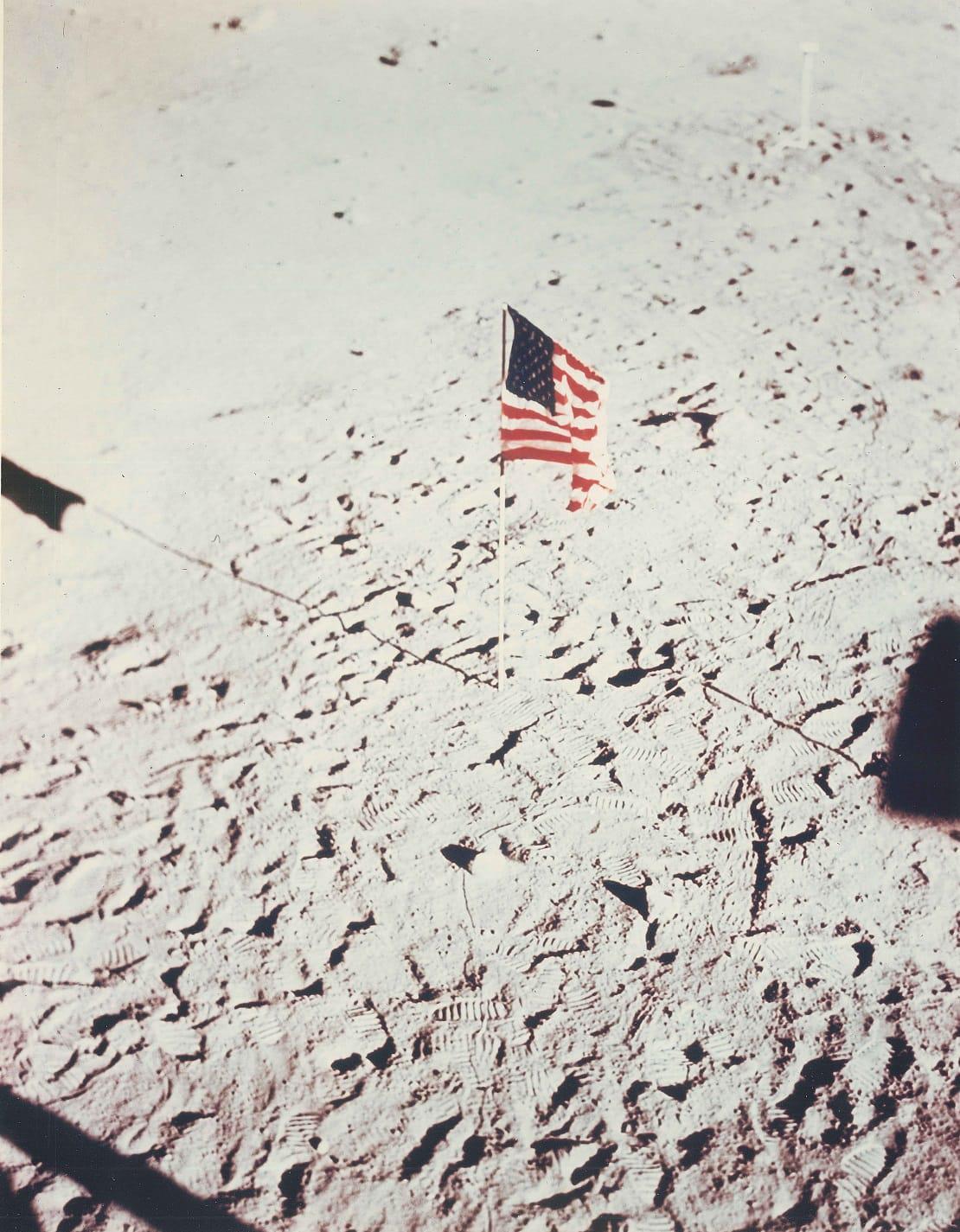

Eight years later, on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human being to step on the moon. Armstrong and two other American astronauts returned safely to Earth four days later.

The fulfillment of Kennedy’s promise was in no small part due to the efforts of the newly formed government agency, the National Aeronautical and Space Administration. But NASA didn’t achieve the “giant leap for mankind” on its own. NGA predecessor agencies also played a key role in the United States’ moon exploration efforts by creating detailed maps and charts of the lunar surface.

Moon photos vs. moon maps

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik the first artificial satellite to orbit the Earth. The success of Sputnik sparked the United States to re-evaluate its own space exploration efforts which resulted in the creation of NASA in 1958.

But as a new agency, NASA didn’t have the personnel or expertise to map the surface of its desired destination, the moon, said Raymond Helmering, Ph.D., former lunar mapping technical project manager for the U.S. Air Force Aeronautical Chart and Information Center.

NASA also wasn’t supposed to duplicate capabilities other federal agencies already held, he said.

In 1959, NASA funded a joint effort by ACIC in St. Louis and the U.S. Army Map Service in Washington, D.C., two NGA predecessor agencies, to collect data to map the surface of the moon. Fortunately for NASA, ACIC and AMS had already anticipated the need for lunar maps to support moon exploration and were already working on the task.

Maps of the moon had existed for centuries before ACIC and AMS started working on their own lunar maps. In 1609, English mapmaker Thomas Harriot drew the first known maps of the moon with his telescope.

As centuries passed improved technology and photography enabled more detailed images of the moon to be captured.

But even the most detailed photographs cannot convey the moon’s surface features as accurately or usefully as a cartographer can with a map.

“A map generally has a high level of accuracy associated with it,” Helmering said. “You can determine geographic coordinates from a map and if you use those, you can compute a position.”

The ability to compute positions was vital for NASA to land a spacecraft on the moon said John Unruh, Ph.D., former cartographer and scientist with ACIC.

“Accurate coordinates of the sites needed to be determined in a coordinate system consistent with accurate vehicle orbit information,” Unruh said.

A cartographer can follow specifications to create maps that show only the features that users would find useful, Helmering said.

A cartographer can identify and compensate for distortion in a photo. Many different photographs of the same feature, such as a crater, can be compared to determine its true qualities including height, diameter and depth.

How We Mapped the Moon

There are two main steps to creating a lunar map from photographs, Helmering said.

The first is the assembly. Cartographers, putting together a lunar jigsaw puzzle, used computers to piece together the disparate “snapshots” of moon territory, he said.

“You have to make sure whatever territory appears in one photograph appears again in an adjacent photograph,” he said. “The process to relate all the photographs is not trivial. It’s a mathematical process done with the help of computers.”

Once that was done, cartographers used photo-viewing equipment and computers to make measurements of the details of the photographs, ultimately creating a map.

“There was a cursor that we could move using levers across the photos,” Helmering said. “The computer would record points and determine distances and shapes. It was computer-assisted, but everything was captured by a cartographer.”

Even more detailed photographs of the moon became available in the late 1960s and early 1970s with NASA’s Apollo missions. Apollo mission cameras, from about 100 miles up, were able to photograph the lunar surface at a much higher resolution than cameras from Earth, which were 238,900 miles away. The higher-resolution images allowed for even more intricate maps, Helmering said.

With the Apollo moon orbits, cartographers also could get photographs and map the dark side of the moon, the side that always faces away from Earth, for the first time.

ACIC and AMS produced hundreds of maps for NASA throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. During the 1969 fiscal year, ACIC created more than 300 different cartographic products in support of five Apollo flights. During the 1970 fiscal year, ACIC created approximately 200 products in support of Apollo.

Unruh estimates that up to 200 people at ACIC worked lunar mapping during its peak in the early 1970s, including cartographers, geodesists and personnel from the photo lab, negative engraving and printing.

Included in the hundreds of products made by ACIC and AMS were 3-D plastic topographic maps of potential moon landing sites.

“We would make several for each mission,” Helmering said. “Astronauts would study them and evaluate which would be the best one for landing and the best for doing whatever experiments they wanted to do. Maps we made were used to evaluate those sites and make those final selections.”

‘One Small Step’

Unlike many analysts today at NGA, lunar cartographers at ACIC and AMS in the 1960s and ‘70s were able to talk about their work with their family and friends. And people were interested, Helmering said, because many Americans were captivated by the idea of space exploration.

“The Apollo program was well-publicized,” Helmering said. “The idea of putting a man on the moon was something everyone was talking about.”

Helmering was taking a training course at Ohio State University in July 1969 when Armstrong took his historic first steps on the moon. Helmering remembers watching the event from a TV with about 10 other ACIC trainees in a house in Columbus that he and his wife were renting.

“I had been involved in lunar work for a long time,” Helmering said. “But I wasn’t thinking about that. I was thinking about those guys up there and what that must have been like. It’s hard to figure out how someone has the courage to do that, to walk on the moon, something that had never been done before.

“We were just amazed that we were able to do that; that we were there,” he said. "It was such a great achievement for the country.”

The below images were given to NGA by the family of Mr. Thomas C. Finnie, who served as technical director at the Aeronautical Chart and Information Center - a heritage organization of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Finnie led production of maps for the manned spaceflights and lunar landings and was at Houston mission control when Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon.

The images were reproduced by the ACIC from photographs furnished by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

NGA Historical Collection